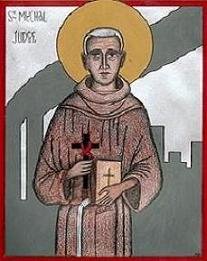

Mychal Fallon Judge, O.F.M. (born Robert Emmett Judge; May 11, 1933 – September 11, 2001), was an American Franciscan friar and Catholic priest who served as a chaplain to the New York City Fire Department.

While serving in that capacity he was killed, becoming the first certified fatality of the September 11, 2001, attacks.

Mychal’s Prayer: Lord, take me where You want me to go,let me meet who You want me to meet,tell me what You want me to say,and keep me out of Your way.

“You know what I want for Christmas? You know what I really want? Absolutely nothing! I have everything in the world.”

Those words of Father Mychal Judge, O.F.M., characterize the simplicity of the New York City Fire Department chaplain killed during a rescue mission immediately following the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center attack. Chaplain to the department since 1992, the 68-year-old died in a hail of steel and concrete as he anointed a firefighter and a fallen office worker. Father Judge became the first officially recorded fatality following the attack.

His close friend, Michael Duffy, O.F.M., remembers how Father Judge would joke with him about his wish list every gift-giving season. After saying he wanted nothing, says Father Duffy, “he would go on for 10 minutes, listing all the blessings he was given: his family, his friends. He loved his Franciscan priesthood, his work with the fire department, his health, his exciting life. Then he’d always wind up almost in tears, saying, ‘I don’t deserve it! Why is God doing this to me?’ He really believed that.”

The image of tearful rescue workers removing Judge’s body from the pre-collapse scene at the World Trade Center spanned the pages of newspapers and magazines in the days following September 11. A more serene image of Father Judge in his habit, gazing out upon the sea before a prayer service in July 2000, accompanied other national stories. There were literally hundreds of heroes like Father Judge, who lost their lives trying to save others.

Father Duffy, grief-stricken, nonetheless received the call to preach at his friend’s funeral at St. Francis of Assisi Church in midtown Manhattan. Judge himself had chosen Duffy as homilist on a form that all friars fill out with instructions for their funeral Mass. “I was so distraught that, the day before, I was going to tell our provincial minister that I couldn’t do it. Then I thought, Mychal would kill me if I don’t do it. So I turned to prayer and asked friends to pray for me. What followed was the work of the Holy Spirit: The day before I had nothing to say and no way to say it. But whatever I said affected lots and lots of people.”

With Cardinal Edward Egan presiding, the September 15 Mass was attended by about 3,000. Among the congregation were city officials, former President Bill Clinton and New York Senator Hillary Clinton, along with their daughter, Chelsea. Duffy’s homily was broadcast worldwide over three TV networks. New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani had attended the wake.

Humble Beginnings

Perhaps Mychal Judge’s uncertainty about his many blessings, his sense of unworthiness, came from his humble beginnings. Or maybe it was from his simple ministry of presence among victims and firefighters, while his fellow friars accomplished what he considered more influential ministries. In late-night phone calls, he would tell his friend Duffy, director of St. Francis Inn, a well-known Philadelphia soup kitchen, “You are doing such important things. I don’t do anything.”

Born in Brooklyn May 11, 1933, Judge was the son of two Irish immigrants from County Leitrim. The seeds of suffering were planted early when at age six he watched his father die from a long illness. To help his mother and two sisters make ends meet, he shined shoes at Penn Station (in the vicinity of St. Francis Church), ran errands and did odd jobs. Responding to his calling amidst the care and attention of the friars, he entered the Franciscans in 1954, made his final profession in 1958 and was ordained in 1961.

He served as pastor of two New Jersey parishes named after St. Joseph: one in East Rutherford, another one in West Milford.

When Duffy and Judge were stationed together at St. Joseph’s in East Rutherford, Duffy was newly ordained (September 11, coincidentally, 1971); Judge had been a priest 10 years and was teaching him the ropes. That was the beginning of their lifelong friendship.

Friar Judge was pastor in West Milford during what was described by The Bergen County Record (New Jersey) as perhaps the most trying times in the town’s history. In a few years’ period, five teens had committed suicide and two others had died in alcohol-related accidents. Father Judge reached into his own experience of suffering and told people, according to the Record, “When tragedies strike us at any early age, maybe religion takes on a greater meaning. The closer the tragedy is to our heart and home, the more likely faith is to form, because we’ve been tested and tried, and from that comes faith.”

Even during his New Jersey years, his love of firefighting was evident: “He was a real fire buff” who loved firefighters and their jobs, according to the Paterson, New Jersey, fire chief.

Before his West Milford assignment, he also had served at Sacred Heart in Rochelle Park, New Jersey. Between parish assignments, he served as assistant to the president at Siena College in Loudonville, New York. He was assigned to St. Francis of Assisi in 1986 and became a fire chaplain in 1992.

“I always wanted to be a priest or a fireman; now I’m both,” Father Judge told coauthor of this story John Zawadzinski some years ago. “I had to bust my tail to get this habit, so I wear it always. I wanted to be a Franciscan so bad. I have absolutely no regrets.” (He did, for safety, wear a chaplain’s uniform when he was on duty for the fire department.)

Man of Compassion

St. Francis of Assisi comes to mind when Father Duffy thinks of his friend Mychal: “Bonaventure writes that Francis had a certain natural bent for compassion. I think Mychal Judge did, too. That’s what made him such a good Franciscan. He just felt so bad for people who were not cared for.”

So many people loved Judge, recalls Duffy, because he “treated everyone like family.” At funerals, he never just opened the book and started praying for people. He made it really personal. “Countless people told me that on birthdays, anniversaries, dates of sobriety—whatever—they would get a little note from him. He must have kept a huge calendar! In everyone’s lives, whatever was significant, he’d write them a little note about it or give them a telephone call. Everyone considered him family.”

Duffy remembers that, outside the Judge funeral, where the overflow crowd had watched and listened via closed-circuit TV and loudspeakers, one of the homeless street people said, “That priest didn’t hide in the sanctuary; he brought the sanctuary out to us.”

Mychal Judge held no distinction between himself and the people, recalls Duffy. “Even though initially a person might approach him as pastor, chaplain, whatever, within 30 seconds all of those titles just fell down and he was just a friend. He wasn’t afraid gently to mention God’s presence.”

This was evident in his love of blessing people “whether they wanted it or not,” recalls Duffy, “with his big, thick Irish hands.” After gaining their consent (“They couldn’t say no!”), “He’d put his big hands on, say, a little old lady’s head and press down until I thought he was going to break her poor little neck.” He would look up to God with raised eyebrows and pray that God would bless her and keep her in peace. “By the end she’d be crying; she’d love it,” Duffy says.

When a pregnant couple approached him, he blessed the baby in the womb. When a troubled couple came to him, says Duffy, “He’d just put his arms around both of them, put his head between their heads, and whisper a blessing.”

Father Mychal was known also for his ministry to those suffering from AIDS, even years back when very few people would go near an AIDS patient. Often, at the end of long days, Fathers Judge and Duffy would talk by phone, sharing experiences. During one of those conversations, Duffy recalls Mychal telling him about an encounter with a particularly difficult situation. This was in the days before medications had been developed to help stem the effects of AIDS. Father Mychal had gone to visit a man who was in such advanced illness that no one would go near him because of the stench.

“Mychal said to me, ‘You know, no one touches the man. He must feel so lonely.’ So he’d go visit him, and hold his hand. He told me that even once he bent over and kissed him on the forehead because he felt so bad that no one would come near him.

“He was not an administrator, and he was not an organizer,” admits Duffy with a chuckle. “We once had a janitor who couldn’t even sweep!” After much urging from his assistants, Judge went off to the man’s house to break the news of his dismissal, only returning to report, “‘Oh, I think if he had just six more months with us’….He didn’t have the heart to fire him!”

During their last phone conversation, Duffy told his mentor-turned-brother about some of his recent work in Philadelphia with the Franciscan volunteer program. Again, Judge poured on the praise for his brother and bemoaned his own lack of initiative. “But while we’re running around giving retreats and organizing things and making soup, he spent his whole life relating to people,” laments Duffy.

Mychal Judge never built a church or a school, or raised a lot of money, says Duffy. “What he did was build a kingdom spiritually, so people feel close to God. You can’t measure that, and you can’t see that. He didn’t realize that that was his gift. But that was evident in the thousands of people who came out to his wake and to his funeral.”

Where the Action Is

Mychal Judge didn’t seek out the limelight, but when it came to him, he relished it, recalls Duffy.

Once there was a hostage situation in Carlstadt, New Jersey, near West Milford. A distraught man had his wife and child at gunpoint in the upper floor of his house. Father Judge arrived first. “When I got there,” recalls Duffy, “I saw Mychal atop a ladder, holding his habit in one hand so he wouldn’t trip, with his other hand on the ladder. He was just so gently talking to the guy inside, telling the man, ‘We can go talk this over. We can go have a cup of coffee. This isn’t the way to handle things. Come on down.’

“Sure enough, the man put the gun down. We expected to hear a gunshot, but it all turned out peacefully.” That’s how he was, says Duffy: “He inserted himself right where the action was, and then he would somehow bring about peace.”

Did he have nerves of steel? “Sometimes I think he didn’t know any better,” says Duffy with a laugh. “He probably didn’t even realize that he was the one who could get hurt! He just saw the need, and that’s what drove him.”

In 1986, newly assigned to Manhattan, Father Judge was called to Bellevue Hospital to say Mass for New York City police officer Steven McDonald, who was left paralyzed from the neck down after being shot by a 15-year-old he was questioning in Central Park.

“When I first saw him, he was just lying in bed, motionless,” Father Judge told coauthor Zawadzinski this past July. “He was in bad shape, but determined to live.”

In the days and years following the shooting, Father Judge became ex-tremely close to McDonald, his wife, Patti Ann, and their son, Conor. The priest also had the opportunity to travel with McDonald during a number of speaking engagements in the United States and Northern Ireland.

“He was my idea of what a priest should be,” says McDonald. “Above all, he was a living example of Jesus Christ. I’m not sure what I’m going to do without him.”

Back in 1996, McDonald had called Father Judge to inform him about the crash of TWA flight 800 off Long Island in which all 230 people aboard were killed. For more than two weeks straight, Father Judge drove daily from Manhattan to the Ramada Inn near J.F.K. Airport. There he spent 12 hours a day consoling friends and families who had lost loved ones. He also celebrated Mass every other day, participated in counseling sessions for people of all denominations and organized ecumenical memorial prayer services for the victims’ families and TWA personnel.

“When that call came through, it was the Lord calling me somehow,” he told coauthor Zawadzinski some years ago, during a visit to his third-floor room at the friary, which overlooks Engine 1/Ladder 24.

A Hero’s Death

Father Judge parked his fire-department chaplain’s car at Engine 1/Ladder 24 and often took his meals with those firefighters (six of whom died in the World Trade Center attack). When there was an emergency, recalls Duffy, “He would throw caution to the wind. But sometimes I don’t think he knew it was there! He would just go help.”

When tragedy struck on September 11, Father Brian Carroll, O.F.M., went up to Father Judge’s room to inform him that a plane had just crashed into one of the World Trade Center towers. Father Carroll recalls that Father Judge quickly took off his Franciscan habit, changed into his chaplain’s uniform and headed for the door. That was the last time the friar would see his friend alive.

“Mayor Giuliani recalls that they were both down there very early in the event and the mayor saw him run by with the firemen,” says Father Duffy. “Giuliani says he grabbed his arm and stopped the friar, saying, ‘Mychal, please pray for us.’ And Mychal just looked at him with a big grin and said, ‘I always do!’ And then he turned and ran off with his firefighters, right to the tower, and that’s where he died.”

There were conflicting early reports of the exact circumstances of Judge’s death. Cassian Miles, O.F.M., communications director for the Holy Name Province, confirmed with the fire department battalion leader on-site at the World Trade Center that Mychal indeed was anointing a firefighter and the woman who had fallen on the firefighter. Father Judge had removed his helmet in prayer and was struck in the back of the head by falling debris. Judge’s body, according to Father Miles, revealed severe injury to the back of the head.

Duffy, in his homily, told what happened next:”The firemen took his body and because they respected and loved him so much, they didn’t want to leave it in the street. So they quickly carried it into a church and not just left it in the vestibule, they went up the center aisle. They covered it with a sheet. And on the sheet, they placed his stole and his fire badge. And then they knelt down and they thanked God. And then they rushed back to continue their work.

“I picture Mychal Judge’s body there in that church in the sanctuary, realizing that the firefighters brought him back to the Father in the Father’s house. The words come to me, ‘I am the good shepherd, and the good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. Greater love than this no man hath than to lay down his life for his friends.’”

In the numb days following the catastrophe, his brother firefighters from Engine 1/Ladder 24 expressed their gratitude for his life among them. Captain Kenneth Herb, a 22-year veteran, says, “I could always go to him with my problems. He was with us 100 percent of the time.” Brian Thomas, a 14-year veteran, fondly recalls, “Father Mychal was the kindest guy in the world. He had such a way with words! When he spoke in public, it was very relaxing—I wish he were here with us now. He always had time for everyone.”

Our ministry was established in his image. Open, humble, and caring, no matter where you find yourself in this world, or on your journey.